|

|

| Korean J Anesthesiol > Volume 75(4); 2022 > Article |

|

Interfascial plane blocks and associated nomenclature are currently popular topics in the field of anesthesia. While several novel plane blocks have been described, cadaveric studies on the spread of novel blocks are important for determining appropriate applications [1]. Recently, Tulgar et al. [2] defined the thoracoabdominal nerve block using a perichondral approach (TAPA). They reported that local anesthetic (LA) administered on the upper and lower aspect of the 9th through the 10th costal cartilages would block both the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches, thus providing abdominal analgesia. After describing the TAPA, the authors also redefined the approach, naming it the modified TAPA (M-TAPA). They reported that administering LA only to the lower surface of the costal cartilage would provide successful analgesia similar to that provided by the TAPA [3]. In the literature, there are some case reports and observational studies on the TAPA and M-TAPA [2,3]; however, to the best of our knowledge, no reliable cadaveric investigation has demonstrated the spread of these blocks. Therefore, in this cadaveric investigation, we aimed to evaluate the areas of spread associated with the TAPA and M-TAPA. This study was approved by the Istanbul Medipol University Ethics and Research Committee (Decision No. 36, 06.01.2022).

One fresh human male cadaver was obtained from Istanbul Medipol University. Injections were performed by two investigators with 10 and 20 years of experienced in administering regional anesthesia. With the cadaver in the supine position, the M-TAPA was performed on the right side, and the TAPA was performed on the left side. The blocks were performed under ultrasound guidance using a linear transducer. The transducer was placed at the costochondral angle in the sagittal view and then advanced to view the lower side of the chondrium. For the TAPA, 20 ml of 0.25% methylene blue dye was injected into both the upper and lower sides of the chondrium (40 ml total). For the M-TAPA, 40 ml of 0.25% methylene blue dye was injected into the lower side of the chondrium.

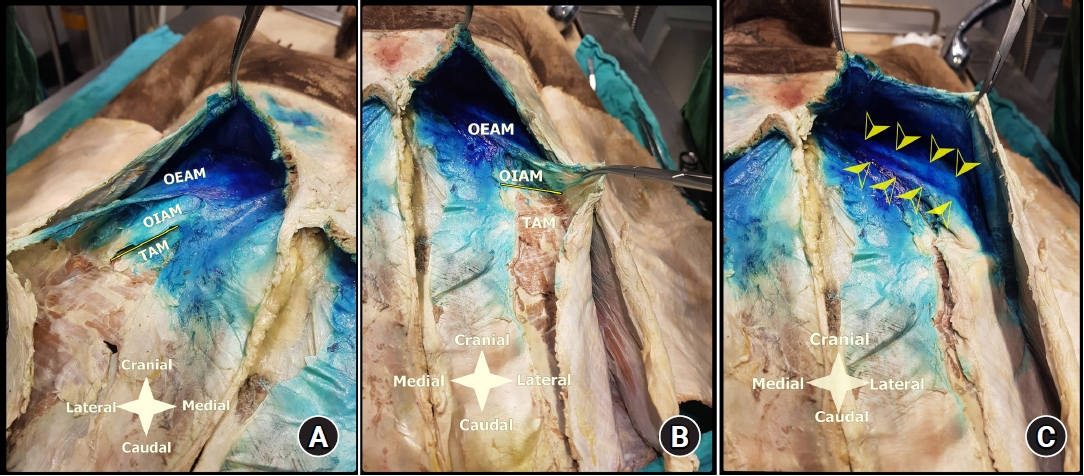

An anatomical dissection was performed 30 min after the procedure. For both the TAPA and M-TAPA, the dye had spread over the lower surface of the upper part of the rectus abdominis and over the thoracoabdominal nerve on both sides. The lower surface of the external abdominal oblique muscle (EAOM) was completely stained with the dye (over the 8th, 9th, and 10th ribs), and so were the upper and lower surfaces of the internal abdominal oblique muscle (IAOM). Additionally, the dye had spread over the upper surface of the costal margin and from T4 to T11ŌĆōT12 on both sides. However, the dye spread over the transverse abdominis muscle (TAM) to a greater degree with the M-TAPA compared with the TAPA (limited to the upper part of the muscle) (Figs. 1A and 1B).

Thoracoabdominal nerves are thoracic spinal nerves with ventral and dorsal branches. Sensorial and muscular innervation of the abdomen is provided by the anterior primary rami of T7ŌĆōT12, which exit through the intercostal areas and enter the plane between the IAOM and TAM (i.e., the transverse abdominis plane [TAP]). The intercostal nerves pass just below the costal cartilage and terminate at the TAP in the abdominal region [2ŌĆō4]. The anterior primary rami of T10ŌĆō12 enter the TAP at the mid-axillary line, which is why additional posterior block applications may fail. The sixth and ninth nerves enter the TAP at the level of the anterior axillary line, which can help explain the failure of the lateral and posterior TAP blocks in the upper abdomen [4]. The TAM arises from the inner aspect of the costal margin, while the IAOM arises from the lower aspects of the costal cartilages of the 4 ribs, and the EAOM arises from the outer aspects of the 5th through the 12th ribs. Therefore, injecting LA at the point where these three muscles intersect would provide abdominal analgesia through thoracoabdominal nerve blockage [2ŌĆō4]. Aikawa et al. [5], in their study, evaluated sensory loss after performing the M-TAPA in patients undergoing gynecological surgery. In that study, the authors reported that the M-TAPA provided limited dermatomal coverage, with greater anterior sensorial loss compared with lateral sensorial loss. In contrast to the clinical results of the study conducted by Aikawa et al., the dye was found to have spread between T4 and T11ŌĆō12 in our cadaveric study. Notably, these authors used 25 ml of the LA, while we used 40 ml of dye.

In conclusion, multiple factors may affect the success of plane blocks. A high-volume M-TAPA may be preferable since fascial plane blocks are volume-related. Based on our results, both the TAPA and M-TAPA may provide analgesia following various abdominal procedures. However, the M-TAPA may provide greater spread over the TAM compared with the TAPA. Since the thoracoabdominal nerves enter the subcutaneous area in the anterior abdominal wall as the anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of the skin, TAPA blocks may be a good alternative for abdominal analgesia due to its region of spread. The literature shows successful analgesia associated with the TAPA for several surgical procedures such as abdominal and gynecological laparoscopic surgery [2,3,5]. However, there may be limitations related to volume. Therefore, further cadaveric and clinical studies are needed to determine the exact effects of the M-TAPA and TAPA blocks.

NOTES

Author Contributions

Bahadir Ciftci (Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Writing ŌĆō original draft; Writing ŌĆō review & editing)

Haci Ahmet Alici (Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Writing ŌĆō review & editing)

Gamze Ansen (Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology)

Bayram Ufuk Sakul (Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology)

Serkan Tulgar (Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Writing ŌĆō original draft; Writing ŌĆō review & editing)

Fig.┬Ā1.

(A) Dissection of the M-TAPA. (B) Dissection of the TAPA. (C) Dye spread of thoracoabdominal nerves. The yellow lines show the thoracoabdominal nerve region between the IAOM and TAM. The yellow arrows show the thoracoabdominal nerves that spread the dye. M-TAPA: modified thoracoabdominal nerves perichondrial approach, TAPA: thoracoabdominal nerves perichondrial approach, EAOM: external abdominal oblique muscle, IAOM: internal abdominal oblique muscle, TAM: transverse abdominis muscle.

References

1. Altiparmak B, Ciftci B, Tekin B, Sakul BU, Alici HA. Is the deep supraspinatus muscle plane block and suprascapular nerve block the same approach? A cadaveric nomenclature study. Korean J Anesthesiol 2022; 75: 193-5.

2. Tulgar S, Senturk O, Selvi O, Balaban O, Ahiskalio─¤lu A, Thomas DT, et al. Perichondral approach for blockage of thoracoabdominal nerves: anatomical basis and clinical experience in three cases. J Clin Anesth 2019; 54: 8-10.

3. Tulgar S, Selvi O, Thomas DT, Deveci U, Ûzer Z. Modified thoracoabdominal nerves block through perichondrial approach (M-TAPA) provides effective analgesia in abdominal surgery and is a choice for opioid sparing anesthesia. J Clin Anesth 2019; 55: 109.